Articles

From time to time we publish Insights. Each Insights is intended to be a thought-provoking piece which often raises controversial themes or discusses misconceptions that we believe are common to many conventional economic analyses. We publish our most recent Insights here on the website.

How the Fed’s tampering with the policy rate sets the shape of the yield curve

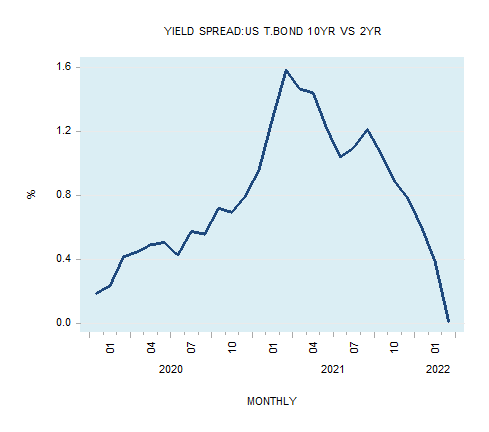

At the end of March this year the difference between the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond and the yield on the 2-year Treasury bond fell to 0.01% from 1.582% at the end of March 2021.

At the end of March this year the difference between the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond and the yield on the 2-year Treasury bond fell to 0.01% from 1.582% at the end of March 2021.

For many commentators, a change in the shape of the yield spread provides an indication regarding where the economy is heading in the months ahead. Thus, an increase in the yield spread raises the likelihood of a possible strengthening in economic activity in the months to come. Conversely, a decline in the yield spread is seen as indicative of a possible economic downturn ahead.

Popular explanation for the shape of the yield curve

A popular explanation regarding the shape of the yield curve is provided by the expectation theory (ET). According to the ET, the expectations for an increase in the short-term interest rate sets in motion an upward sloping yield curve. While the expectations for the decline in the short-term interest rate sets the downward sloping yield curve.

In the ET framework, it is the average of the current and expected short-term rates which determines the current long-term rate. Thus if today’s one year rate is 4% and next year’s one-year rate is expected to be 5%, then the two-year rate today should be 4.5% (4+5):2=4.5. Here the long-term rate, i.e. the two-year rate today, is higher than the short-term (i.e. one year) rate. It follows then that expectations for rises in short-term rates will make the yield curve upward sloping, because long-term rates will be higher than short-term rates.

Conversely, expectations for a decline in short-term rates will result in a downward sloping yield curve, because long-term rates will be lower than short-term rates. If today’s one year rate is 4% and next year’s one-year rate is expected to be 3%, then the two-year rate today should be 3.5% (4+3):2=3.5. The long-term rate (i.e. the two-year rate today) is lower than the short-term rate.

According to the ET whenever investors start to anticipate economic expansion, they also begin to form expectations that the central bank is going to raise short-term interest rates by lifting the policy rate. To avoid capital losses investors will move their money from long-term securities to short-term securities. (A rise in interest rates will have a greater impact on the prices of long-term securities versus short-term securities). This shift will bid short-term securities prices up and their yields down. With respect to long-term securities, the shift of money away will depress their prices and raise their yields. Hence, we have here a decline in short-term yields and a rise in long-term yields – a tendency for an upward sloping yield curve emerges.

Conversely, it is held whenever investors expect an economic slowdown or a recession they also start forming expectations that the central bank will lower short-term interest rates by lowering the policy rate. Consequently, investors will shift their money from short-term securities towards long-term securities. Thus, the selling of short-term assets will result in a fall in their prices and a rise in their yields. A shift of money towards long-term assets will result in the increase in their prices and a decline in their yields. Hence this shift in money raises short-term yields and lowers long-term yields i.e., a tendency for a downward sloping yield curve emerges.

Note again that in the ET framework, the formation of expectations regarding short-term interest rates determines long-term interest rates and in turn, the shape of the yield curve. In the ET framework, given that the central bank determines short-term rates via the policy rate it also follows that in the ET framework interest rates i.e. both short-term and long-term are determined by the central bank. However, does the ET framework make sense?

Does the central bank determine interest rates?

Note that contrary to the ET framework, interest rates are not determined by central bank monetary policy but by individuals time preferences. The phenomenon of interest is the outcome of the fact that individuals assign a greater importance to goods and services in the present versus identical goods and services in the future. The higher valuation is not the result of some capricious behaviour, but on account of the fact that life in the future is not possible without sustaining it first in the present.

As long as the means at an individual’s disposal are just sufficient to accommodate his immediate needs, he is most likely going to assign less importance to future goals. With the expansion of the pool of means, the individual can now allocate some of those means towards the accomplishments of various ends in the future.

As a rule, with the expansion in the pool of means, individuals are then able to allocate more means towards the accomplishment of remote goals in order to improve their quality of life over time. (Individuals could lower their time preference).

With paltry means, an individual can only consider very short-term goals, such as making a basic tool. The meager size of his means does not permit him to undertake the making of more advanced tools. With the increase in the means at his disposal, the individual could consider undertaking the making of better tools.

Again, whilst prior to the expansion of wealth the need to sustain life and wellbeing in the present made it impossible to undertake various long-term projects, with more wealth this has become possible. Note that very few individuals are likely to embark on a business venture, which promises a zero rate of return. The maintenance of the process of life over and above hand to mouth existence requires an expansion in wealth. The wealth expansion implies positive returns.

Observe that the interest rate is just an indicator as it were which reflects individuals’ decisions regarding present consumption versus future consumption. In a free unhampered market, fluctuations in interest rates are going to be in line with changes in consumers’ time preferences. Thus, a decline in the interest rate is going to be in response to the lowering of individuals’ time preferences. Consequently, when businesses observe a decline in the market interest rate they are responding to this by lifting their investment in capital goods in order to be able to accommodate in the future the likely increase in consumer goods demand.

Shape of the yield curve in an unhampered market

According to Ludwig von Mises, in a free unhampered market economy, the natural tendency of the shape of the yield curve is neither towards an upward sloping nor towards a downward sloping but rather towards being horizontal. (Observe that the horizontal yield curve emerges after adjusting for risk.) On this Mises wrote,

The activities of the entrepreneurs tend toward the establishment of a uniform rate of originary interest in the whole market economy. If there turns up in one sector of the market a margin between the prices of present goods and those of future goods, which deviates from the margin prevailing on other sectors, a trend toward equalization is brought about by the striving of businessmen to enter those sectors in which this margin is higher and to avoid those in which it is lower. The final rate of originary interest is the same in all parts of the market of the evenly rotating economy. [Ludwig von Mises: Human Action, third edition p536]

Similarly, Murray Rothbard held that in a free unhampered market economy, an upward sloping yield curve could not be sustained for it would set in motion an arbitrage between short and long-term securities. Funds are going to be shifted from short maturities to long maturities. This would lift short-term interest rates and lower long-term interest rates, resulting in the tendency towards a uniform interest rate throughout the term structure. Arbitrage is likely to prevent the sustainability of a downward sloping yield curve by shifting funds from long maturities to short maturities thereby flattening the curve. [Murray Rothbard: Man, Economy, and State Nash Publishing p 384]

Hence, in a free, unhampered market economy a prolonged upward or downward sloping yield curve cannot be sustained. What then is the mechanism that generates a sustained upward or downward sloping yield curve? We hold that the key factor for this is the central bank tampering with financial markets by means of monetary policies.

How the Fed’s tampering alters the shape of the yield curve

While the Fed can exercise control over short-term interest rates via the federal funds rate, it has lesser control over longer-term rates. In this sense, long-term rates can be seen as reflecting, to a certain degree, the time preferences of individuals. The Fed’s monetary policies disrupt the natural tendency towards uniformity of interest rates along the term structure. This disruption leads to the deviation of short-term rates from the individuals’ time preferences rates as partially mirrored by the less-manipulated long-term rate. This deviation in turn leads to the misallocation of resources and to the boom-bust cycle menace.

As a rule Fed policy makers decide about the interest rate stance in accordance with the observed and the expected state of the economy and price inflation. Thus, whenever the economy is starting to show signs of weakness whilst the rate of increase of various price indexes starts to ease, investors in the market begin to form expectations that in the months ahead the Fed is going to lower its policy interest rate.

As a result, short-term interest rates begin to move lower. The spread between the long-term rates and the short-term rates starts to widen – the process of the development of an upward sloping yield curve is now set in motion. This process however, cannot be maintained without the Fed’s actually lowering the policy interest rate. For the positive sloped yield curve to be sustained the central bank must persist with its easy stance. Should the central bank cease with its easy monetary policy the shape of the yield curve would tend to flatten.

Equally, whenever economic activity shows signs of strengthening, coupled with a rise in price inflation, investors’ in the market start to form expectations that in the months ahead the Fed is going to lift its policy interest rate. As a result, short-term interest rates begin to move higher. The spread between the long-term rates and the short-term rates starts to decline – the process of the development of a downward sloping yield curve is now set in motion. This process however, cannot be maintained without the Fed actually lifting the policy interest rate.

Observe that the downward sloping yield curve emerges on account of a tighter monetary stance and can only be sustained if the Fed persists with its tighter monetary policy. Should the central bank abandon the tighter stance this would lead to the flattening of the yield curve. Note again that the Fed’s tampering with short-term interest rates distorts the natural tendency of the yield curve to gravitate towards the horizontal shape.

Why changes in the shape of the yield curve precede the pace of economic activity

Whenever the central bank reverses its monetary stance and alters the shape of the yield curve it sets in motion either an economic boom or an economic bust. These booms and busts arise with lags – they are not immediate. The reason for this is because the effect of a change in the monetary policy shifts gradually from one market to another market, from one individual to another individual. For instance, when, during an economic expansion, the central bank raises its interest rates and flattens the yield curve, the effect is minimal as economic activity is still dominated by the previous easy monetary stance. It is only later on, once the tighter stance begins to dominate the scene that economic activity begins to weaken.

The yield spread and the money supply growth rate

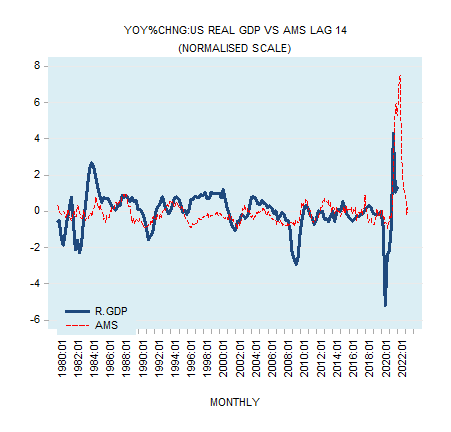

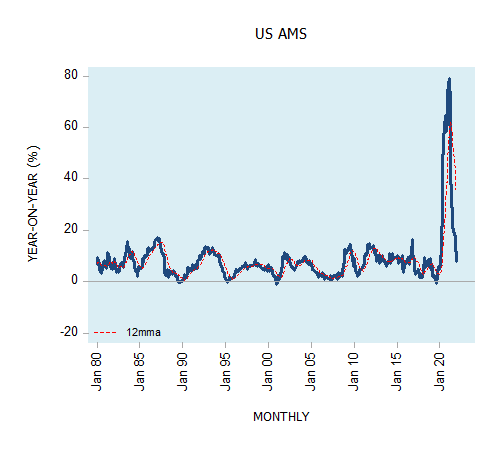

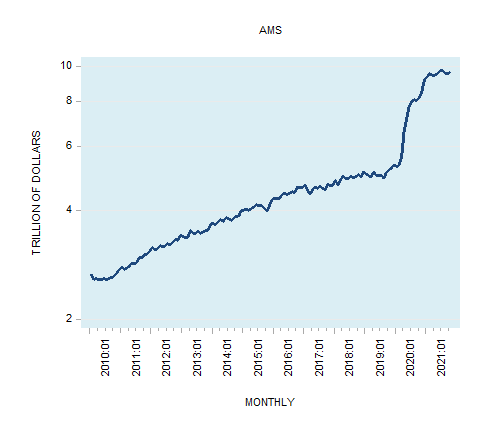

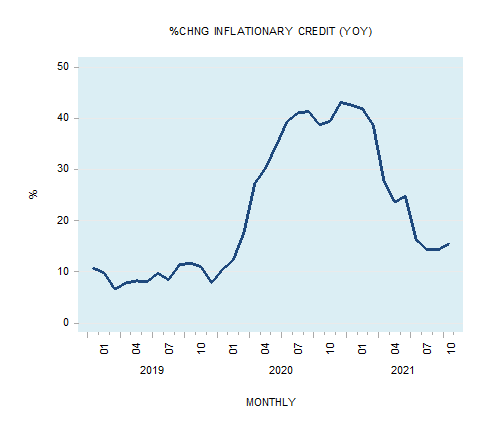

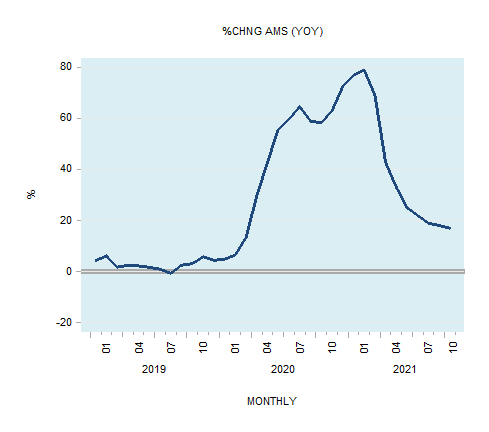

As a rule, an upward sloping yield curve (because of the lowering of short-term interest rates by the Fed) is associated with a strengthening in the generation of money out of “thin air” and in the strengthening in the momentum of our monetary measure AMS. A downward sloping yield curve (because of the tighter interest rate stance by the Fed) is associated with a weakening in the pace of generation of money out of “thin air” and hence with a decline in the annual growth rate of AMS.

This means that fluctuations in the momentum of AMS correspond to the relevant yield spread. Thus, a decline in the momentum of AMS, which corresponds to the downward sloping yield curve, raises the likelihood that after a time lag a decline in economic activity will emerge. An increase in the momentum of AMS, which corresponds to the upward sloping yield curve, raises the likelihood that after a time lag an increase in economic activity will take place.

Now, the yearly growth rate of real GDP closed at 5.5% in Q4 2021 against 4.9% in Q3 and -2.3% in Q4 2020. Based on the current downward sloping yield curve and the corresponding downward momentum of AMS we can suggest that the annual growth rate of economic activity in terms of real GDP is likely to come under downward pressure in the months ahead (see chart).

Popular explanation for the shape of the yield curve

A popular explanation regarding the shape of the yield curve is provided by the expectation theory (ET). According to the ET, the expectations for an increase in the short-term interest rate sets in motion an upward sloping yield curve. While the expectations for the decline in the short-term interest rate sets the downward sloping yield curve.

In the ET framework, it is the average of the current and expected short-term rates which determines the current long-term rate. Thus if today’s one year rate is 4% and next year’s one-year rate is expected to be 5%, then the two-year rate today should be 4.5% (4+5):2=4.5. Here the long-term rate, i.e. the two-year rate today, is higher than the short-term (i.e. one year) rate. It follows then that expectations for rises in short-term rates will make the yield curve upward sloping, because long-term rates will be higher than short-term rates.

Conversely, expectations for a decline in short-term rates will result in a downward sloping yield curve, because long-term rates will be lower than short-term rates. If today’s one year rate is 4% and next year’s one-year rate is expected to be 3%, then the two-year rate today should be 3.5% (4+3):2=3.5. The long-term rate (i.e. the two-year rate today) is lower than the short-term rate.

According to the ET whenever investors start to anticipate economic expansion, they also begin to form expectations that the central bank is going to raise short-term interest rates by lifting the policy rate. To avoid capital losses investors will move their money from long-term securities to short-term securities. (A rise in interest rates will have a greater impact on the prices of long-term securities versus short-term securities). This shift will bid short-term securities prices up and their yields down. With respect to long-term securities, the shift of money away will depress their prices and raise their yields. Hence, we have here a decline in short-term yields and a rise in long-term yields – a tendency for an upward sloping yield curve emerges.

Conversely, it is held whenever investors expect an economic slowdown or a recession they also start forming expectations that the central bank will lower short-term interest rates by lowering the policy rate. Consequently, investors will shift their money from short-term securities towards long-term securities. Thus, the selling of short-term assets will result in a fall in their prices and a rise in their yields. A shift of money towards long-term assets will result in the increase in their prices and a decline in their yields. Hence this shift in money raises short-term yields and lowers long-term yields i.e., a tendency for a downward sloping yield curve emerges.

Note again that in the ET framework, the formation of expectations regarding short-term interest rates determines long-term interest rates and in turn, the shape of the yield curve. In the ET framework, given that the central bank determines short-term rates via the policy rate it also follows that in the ET framework interest rates i.e. both short-term and long-term are determined by the central bank. However, does the ET framework make sense?

Does the central bank determine interest rates?

Note that contrary to the ET framework, interest rates are not determined by central bank monetary policy but by individuals time preferences. The phenomenon of interest is the outcome of the fact that individuals assign a greater importance to goods and services in the present versus identical goods and services in the future. The higher valuation is not the result of some capricious behaviour, but on account of the fact that life in the future is not possible without sustaining it first in the present.

As long as the means at an individual’s disposal are just sufficient to accommodate his immediate needs, he is most likely going to assign less importance to future goals. With the expansion of the pool of means, the individual can now allocate some of those means towards the accomplishments of various ends in the future.

As a rule, with the expansion in the pool of means, individuals are then able to allocate more means towards the accomplishment of remote goals in order to improve their quality of life over time. (Individuals could lower their time preference).

With paltry means, an individual can only consider very short-term goals, such as making a basic tool. The meager size of his means does not permit him to undertake the making of more advanced tools. With the increase in the means at his disposal, the individual could consider undertaking the making of better tools.

Again, whilst prior to the expansion of wealth the need to sustain life and wellbeing in the present made it impossible to undertake various long-term projects, with more wealth this has become possible. Note that very few individuals are likely to embark on a business venture, which promises a zero rate of return. The maintenance of the process of life over and above hand to mouth existence requires an expansion in wealth. The wealth expansion implies positive returns.

Observe that the interest rate is just an indicator as it were which reflects individuals’ decisions regarding present consumption versus future consumption. In a free unhampered market, fluctuations in interest rates are going to be in line with changes in consumers’ time preferences. Thus, a decline in the interest rate is going to be in response to the lowering of individuals’ time preferences. Consequently, when businesses observe a decline in the market interest rate they are responding to this by lifting their investment in capital goods in order to be able to accommodate in the future the likely increase in consumer goods demand.

Shape of the yield curve in an unhampered market

According to Ludwig von Mises, in a free unhampered market economy, the natural tendency of the shape of the yield curve is neither towards an upward sloping nor towards a downward sloping but rather towards being horizontal. (Observe that the horizontal yield curve emerges after adjusting for risk.) On this Mises wrote,

The activities of the entrepreneurs tend toward the establishment of a uniform rate of originary interest in the whole market economy. If there turns up in one sector of the market a margin between the prices of present goods and those of future goods, which deviates from the margin prevailing on other sectors, a trend toward equalization is brought about by the striving of businessmen to enter those sectors in which this margin is higher and to avoid those in which it is lower. The final rate of originary interest is the same in all parts of the market of the evenly rotating economy. [Ludwig von Mises: Human Action, third edition p536]

Similarly, Murray Rothbard held that in a free unhampered market economy, an upward sloping yield curve could not be sustained for it would set in motion an arbitrage between short and long-term securities. Funds are going to be shifted from short maturities to long maturities. This would lift short-term interest rates and lower long-term interest rates, resulting in the tendency towards a uniform interest rate throughout the term structure. Arbitrage is likely to prevent the sustainability of a downward sloping yield curve by shifting funds from long maturities to short maturities thereby flattening the curve. [Murray Rothbard: Man, Economy, and State Nash Publishing p 384]

Hence, in a free, unhampered market economy a prolonged upward or downward sloping yield curve cannot be sustained. What then is the mechanism that generates a sustained upward or downward sloping yield curve? We hold that the key factor for this is the central bank tampering with financial markets by means of monetary policies.

How the Fed’s tampering alters the shape of the yield curve

While the Fed can exercise control over short-term interest rates via the federal funds rate, it has lesser control over longer-term rates. In this sense, long-term rates can be seen as reflecting, to a certain degree, the time preferences of individuals. The Fed’s monetary policies disrupt the natural tendency towards uniformity of interest rates along the term structure. This disruption leads to the deviation of short-term rates from the individuals’ time preferences rates as partially mirrored by the less-manipulated long-term rate. This deviation in turn leads to the misallocation of resources and to the boom-bust cycle menace.

As a rule Fed policy makers decide about the interest rate stance in accordance with the observed and the expected state of the economy and price inflation. Thus, whenever the economy is starting to show signs of weakness whilst the rate of increase of various price indexes starts to ease, investors in the market begin to form expectations that in the months ahead the Fed is going to lower its policy interest rate.

As a result, short-term interest rates begin to move lower. The spread between the long-term rates and the short-term rates starts to widen – the process of the development of an upward sloping yield curve is now set in motion. This process however, cannot be maintained without the Fed’s actually lowering the policy interest rate. For the positive sloped yield curve to be sustained the central bank must persist with its easy stance. Should the central bank cease with its easy monetary policy the shape of the yield curve would tend to flatten.

Equally, whenever economic activity shows signs of strengthening, coupled with a rise in price inflation, investors’ in the market start to form expectations that in the months ahead the Fed is going to lift its policy interest rate. As a result, short-term interest rates begin to move higher. The spread between the long-term rates and the short-term rates starts to decline – the process of the development of a downward sloping yield curve is now set in motion. This process however, cannot be maintained without the Fed actually lifting the policy interest rate.

Observe that the downward sloping yield curve emerges on account of a tighter monetary stance and can only be sustained if the Fed persists with its tighter monetary policy. Should the central bank abandon the tighter stance this would lead to the flattening of the yield curve. Note again that the Fed’s tampering with short-term interest rates distorts the natural tendency of the yield curve to gravitate towards the horizontal shape.

Why changes in the shape of the yield curve precede the pace of economic activity

Whenever the central bank reverses its monetary stance and alters the shape of the yield curve it sets in motion either an economic boom or an economic bust. These booms and busts arise with lags – they are not immediate. The reason for this is because the effect of a change in the monetary policy shifts gradually from one market to another market, from one individual to another individual. For instance, when, during an economic expansion, the central bank raises its interest rates and flattens the yield curve, the effect is minimal as economic activity is still dominated by the previous easy monetary stance. It is only later on, once the tighter stance begins to dominate the scene that economic activity begins to weaken.

The yield spread and the money supply growth rate

As a rule, an upward sloping yield curve (because of the lowering of short-term interest rates by the Fed) is associated with a strengthening in the generation of money out of “thin air” and in the strengthening in the momentum of our monetary measure AMS. A downward sloping yield curve (because of the tighter interest rate stance by the Fed) is associated with a weakening in the pace of generation of money out of “thin air” and hence with a decline in the annual growth rate of AMS.

This means that fluctuations in the momentum of AMS correspond to the relevant yield spread. Thus, a decline in the momentum of AMS, which corresponds to the downward sloping yield curve, raises the likelihood that after a time lag a decline in economic activity will emerge. An increase in the momentum of AMS, which corresponds to the upward sloping yield curve, raises the likelihood that after a time lag an increase in economic activity will take place.

Now, the yearly growth rate of real GDP closed at 5.5% in Q4 2021 against 4.9% in Q3 and -2.3% in Q4 2020. Based on the current downward sloping yield curve and the corresponding downward momentum of AMS we can suggest that the annual growth rate of economic activity in terms of real GDP is likely to come under downward pressure in the months ahead (see chart).

Conclusions

A change in the shape of the yield curve emerges in response to Fed’s policy makers setting targets to the federal funds rate. We suggest that changes in the growth rate of money supply correspond to a given shape of the yield curve. An upward sloping yield curve corresponds to a rising momentum of the money supply. The downward sloping yield curve corresponds to the declining annual growth rate of money supply. Based on this we hold that currently a visible downtrend in the spread between the yields on the 10-year and the 2-year Treasuries does not bode well for economic activity in the months ahead.

Again, we hold that both the upward and the downward sloping yield curves are the outcome of the central bank tampering with financial markets. This tampering results in the deviation of market interest rates from the time preference rates. Consequently, this results in the boom-bust cycle menace.

We also suggest that in a free market in the absence of the central bank, after adjusting for risk, the shape of the yield curve is going to be neither upward nor downward sloping but rather horizontal.

A change in the shape of the yield curve emerges in response to Fed’s policy makers setting targets to the federal funds rate. We suggest that changes in the growth rate of money supply correspond to a given shape of the yield curve. An upward sloping yield curve corresponds to a rising momentum of the money supply. The downward sloping yield curve corresponds to the declining annual growth rate of money supply. Based on this we hold that currently a visible downtrend in the spread between the yields on the 10-year and the 2-year Treasuries does not bode well for economic activity in the months ahead.

Again, we hold that both the upward and the downward sloping yield curves are the outcome of the central bank tampering with financial markets. This tampering results in the deviation of market interest rates from the time preference rates. Consequently, this results in the boom-bust cycle menace.

We also suggest that in a free market in the absence of the central bank, after adjusting for risk, the shape of the yield curve is going to be neither upward nor downward sloping but rather horizontal.

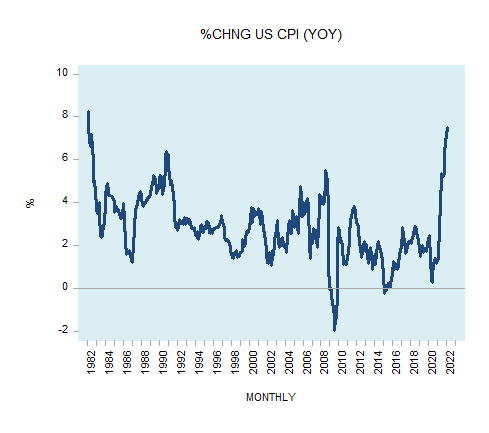

US price inflation highest since 1982

The yearly growth rate in the CPI climbed to 7.5% in January this year from 7% in December and 1.4% in January 2021. The January growth rate was the highest reading since February 1982. We find it extraordinary that most commentators have nothing to say about the role of money in this massive increase in price inflation. After all a price of something is the amount of money, i.e. dollars paid per unit of something. (The number of dollars per one loaf of bread, or the number of dollars per one shirt etc.).

The yearly growth rate in the CPI climbed to 7.5% in January this year from 7% in December and 1.4% in January 2021. The January growth rate was the highest reading since February 1982. We find it extraordinary that most commentators have nothing to say about the role of money in this massive increase in price inflation. After all a price of something is the amount of money, i.e. dollars paid per unit of something. (The number of dollars per one loaf of bread, or the number of dollars per one shirt etc.).

Once money enters a particular market, this means that more money is paid for a product in that market. Alternatively, we can say that the price of a good in this market has gone up. Note again that a price is the number of dollars per unit of something.

Again, when money is injected it enters a particular market. Once the price of a good rises to the level that is perceived as fully valued then the money leaves to another market, which is considered as undervalued. The shift of money from one market to another market is not instantaneous - there is a time lag from increases in money and its effect on the average price increases.

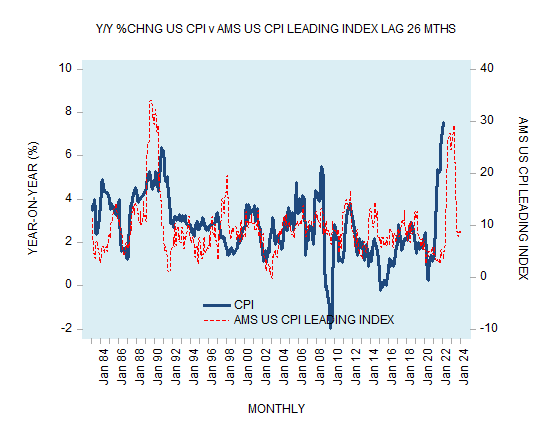

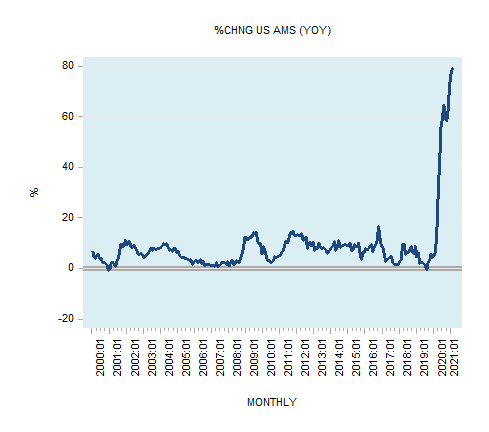

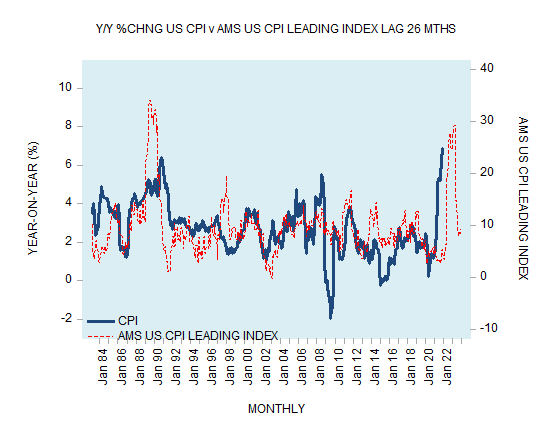

We suggest that because of past massive increases in the money supply, it is not surprising that the growth momentum of prices displays strengthening. Note that the yearly growth rate of our measure of money supply the AMS climbed to 79% in February 2021 from 6.5% in February 2020.

Again, when money is injected it enters a particular market. Once the price of a good rises to the level that is perceived as fully valued then the money leaves to another market, which is considered as undervalued. The shift of money from one market to another market is not instantaneous - there is a time lag from increases in money and its effect on the average price increases.

We suggest that because of past massive increases in the money supply, it is not surprising that the growth momentum of prices displays strengthening. Note that the yearly growth rate of our measure of money supply the AMS climbed to 79% in February 2021 from 6.5% in February 2020.

Why strengthening in economic activity does not cause general increase in prices.

By popular thinking, an increase in economic activity is almost always seen as a trigger for a general rise in prices. However, why should an increase in the production of goods lead to a general increase in prices? If the money stock stays intact, then we will have here a situation of less money per unit of a good — a fall in prices. Only if the pace of money expansion surpasses the pace of increase in the production of goods will we have a general increase in prices. Note that this increase because of the inflation of money and not on account of the increase in the production of goods.

Another popular explanation for a general rise in prices is the increase in wages once the economy is close to the potential output. If the amount of money remains unchanged then it is not possible to raise all the prices of goods and wages. So again, the trigger for a general rise in prices has to be monetary expansion.

What matters is increases in monetary inflation not increases in CPI

We suggest that what matters is not increases in the CPI as such but increases in money supply. Increases in money supply set the process of impoverishment of wealth generators and set the boom-bust cycle menace. Note that increases in the prices of goods and services are just the symptoms of the increases in the money supply. These increases in prices do not cause the diversion of wealth from wealth generators to the holders of money out of “thin air”. Price increases are indicators as it were that tell us that the impoverishment of wealth producers is taking place. (Note that price increases do not always portray the severity of the damage inflicted upon wealth producers).

Once money is injected, it starts the process of impoverishment of wealth producers. Because of the monetary time lag, the impoverishment cannot be arrested immediately. To prevent the further weakening of wealth generators what is required is the closure of all the loopholes for the increases in money supply.

How is the Fed likely to respond to accelerating price inflation?

The massive monetary pumping has generated a gigantic bubble, which projects an impression of economic strength in terms of rebounds in various key indicators such as real GDP. The strength of these indicators is however due to this massive monetary pumping. If anything, this pumping has severely undermined the process of wealth generation by setting a very large misallocation of scarce resources. There is a high likelihood that the percentage of non- wealth generators out of total activity could be strongly above the 50% mark. If Fed officials were to decide to raise interest rates even by a tiny percentage, this could run the risk of generating an economic earthquake. (Note that any tightening is going to undermine bubble activities, which cannot stand on their own feet. These activities require ongoing wealth transfer from wealth generators by means of loose monetary policy of the Fed). Equally, if the Fed were to delay the increase in the policy rate, the decline in the bond market prices likely to burst the bubble.

Hence, we can suggest that the Fed cannot prevent the bursting of the bubble. Only if the pool of savings is still expanding then the Fed has a chance to display an illusory perception that it can grow the economy. Given all the reckless past and present monetary policies, it is quite likely that the pool of savings remains under severe downward pressure. Based on our lagged monetary measure we suggest that price inflation is likely to remain buoyant until the end of this year before a visible decline emerges (see chart).

By popular thinking, an increase in economic activity is almost always seen as a trigger for a general rise in prices. However, why should an increase in the production of goods lead to a general increase in prices? If the money stock stays intact, then we will have here a situation of less money per unit of a good — a fall in prices. Only if the pace of money expansion surpasses the pace of increase in the production of goods will we have a general increase in prices. Note that this increase because of the inflation of money and not on account of the increase in the production of goods.

Another popular explanation for a general rise in prices is the increase in wages once the economy is close to the potential output. If the amount of money remains unchanged then it is not possible to raise all the prices of goods and wages. So again, the trigger for a general rise in prices has to be monetary expansion.

What matters is increases in monetary inflation not increases in CPI

We suggest that what matters is not increases in the CPI as such but increases in money supply. Increases in money supply set the process of impoverishment of wealth generators and set the boom-bust cycle menace. Note that increases in the prices of goods and services are just the symptoms of the increases in the money supply. These increases in prices do not cause the diversion of wealth from wealth generators to the holders of money out of “thin air”. Price increases are indicators as it were that tell us that the impoverishment of wealth producers is taking place. (Note that price increases do not always portray the severity of the damage inflicted upon wealth producers).

Once money is injected, it starts the process of impoverishment of wealth producers. Because of the monetary time lag, the impoverishment cannot be arrested immediately. To prevent the further weakening of wealth generators what is required is the closure of all the loopholes for the increases in money supply.

How is the Fed likely to respond to accelerating price inflation?

The massive monetary pumping has generated a gigantic bubble, which projects an impression of economic strength in terms of rebounds in various key indicators such as real GDP. The strength of these indicators is however due to this massive monetary pumping. If anything, this pumping has severely undermined the process of wealth generation by setting a very large misallocation of scarce resources. There is a high likelihood that the percentage of non- wealth generators out of total activity could be strongly above the 50% mark. If Fed officials were to decide to raise interest rates even by a tiny percentage, this could run the risk of generating an economic earthquake. (Note that any tightening is going to undermine bubble activities, which cannot stand on their own feet. These activities require ongoing wealth transfer from wealth generators by means of loose monetary policy of the Fed). Equally, if the Fed were to delay the increase in the policy rate, the decline in the bond market prices likely to burst the bubble.

Hence, we can suggest that the Fed cannot prevent the bursting of the bubble. Only if the pool of savings is still expanding then the Fed has a chance to display an illusory perception that it can grow the economy. Given all the reckless past and present monetary policies, it is quite likely that the pool of savings remains under severe downward pressure. Based on our lagged monetary measure we suggest that price inflation is likely to remain buoyant until the end of this year before a visible decline emerges (see chart).

Currently market expectations is for the Fed to raise rates this year multiple times with some analyst suggesting a sharp hike as recent as March. At this stage, we do not share the same conviction given our outlook for the continued slowing in economic activity. Given recent volatility in financial markets, we hold that the Fed would prefer to delay any future rate hikes.

Is corporate greed to blame for price increases?

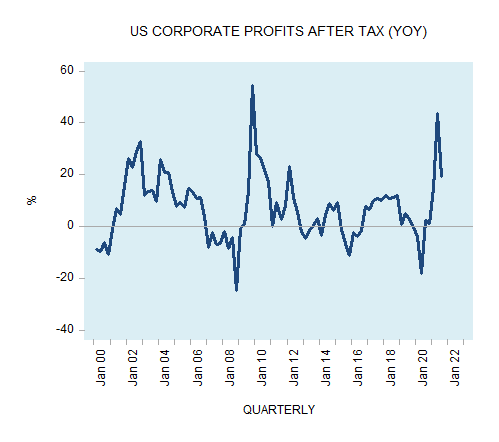

Some commentators attribute the latest sharp increase in the consumer price index (CPI) to businesses pushing prices of goods higher in order to secure higher profits. (See the New York Times article “Democrats Blast Corporate Profits as Inflation Surges”, January 3, 2022). Note that the yearly growth rate of CPI increase jumped to 6.8% in November 2021 from 1.2% in the year before

Meanwhile, the yearly growth rate of corporate profits after tax with inventory valuation adjustment and capital consumption adjustment edged down in Q3 to a still lofty 19.1% after rising by 43.4% in the second quarter.

However, is it true that prices are established by businesses without the consent of consumers?

How prices are established?

As a rule, a supplier sets the price. After all it is the supplier who offers the goods to the buyers. So it is the supplier who must set the price of a good before he presents the good to the buyers.

In order to secure the price that will improve his lot, the price that the supplier sets must cover his direct and indirect costs and provide a margin for profit. By setting the price, the supplier must make as good an estimate as possible regarding whether he will be able to sell his entire supply at the price set.

The process of making the estimate involves the assessment of the possible responses of the buyers and the possible responses of his competitors — other suppliers. If his estimates are accurate then he makes a profit. By making a profit, the supplier expands his pool of resources, which in turn enables him to attain more ends. His standard of living improves.

Observe that while the cost of production in some cases would appear to be the main factor in price determination, this is not so. Ultimately, it is the evaluation of the buyer that dictates whether the price set by the supplier is going to be realized. Every buyer decides in his own context whether the price paid for a good betters his life and well-being.

If the cost of production were the driving factor behind setting market prices then how would we explain the prices of goods that have no cost because they are not produced — goods that are simply there, like undeveloped land?

Likewise, the cost-of-production theory cannot explain the reason for the high prices of famous paintings.

According to Rothbard,

Similarly, immaterial consumer services such as the prices of entertainment, concerts, physicians, domestic servants, etc., can scarcely be accounted for by costs embodied in a product.(Murray N. Rothbard, "The Celebrated Adam Smith," originally in Economic Thought Before Adam Smith: An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic hought, Vol. I, Edward Elgar Press, 1995; Mises Institute, 2006.)

It follows then that businesses striving to make profits cannot cause increases in the prices of goods and services without the consent of consumers.

Defining what price is

A price of a thing is the amount of money paid for the thing, for example the number of dollars per loaf of bread, or the number of dollars per shirt. The key driving factors here are the amount of dollars and the quantity of goods.

Now, with all other things being equal, an increase in the amount of money paid for goods and services implies that the price of these goods and services is going to be higher. More money is now paid for these goods and services.

In the absence of the increase in the amount of money there cannot be a general increase in prices. If a business raises the price of its goods and consumers have agreed to this increase then consumers are going to have less money to spend on other goods, all other things being equal. Hence, we will have here a specific price increase but not general increase in prices.

Increases in money supply is what inflation is all about

By a popular thinking, it is the role of the central bank to guide the economy onto the path of economic and price stability.

If central bank officials form a view that the economy will fall below the path of economic and price stability, then officials are expected to prevent this decline by monetary pumping. Conversely, if officials are of the view that the economy is likely to overshoot the stable path then they are likely to prevent this by reducing their monetary pumping.

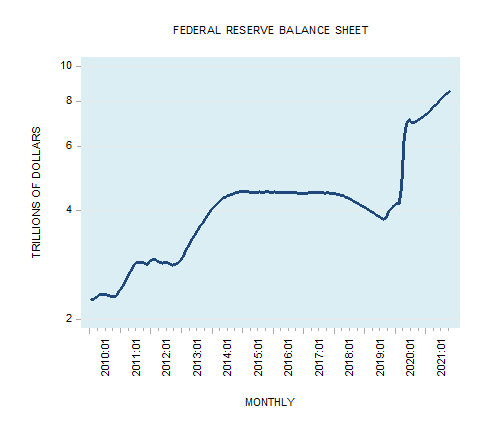

In response to COVID19, and in particular the lockdowns and other restrictions, severe damage to the economy was expected by central bank officials. (The economy was expected to fall strongly below the path of stability). In this case, strong monetary pumping was considered as a welcome move. The strong monetary pumping is believed to have brought the economy onto a stable path.

We suggest that this monetary pumping cannot generate economic stability. The pumping sets in motion an exchange of nothing for something, or the diversion of wealth from wealth generators to the early recipients of the newly pumped money. As a result, this undermines the process of wealth generation and weakens the prospects for economic growth.

As a rule, because of the monetary pumping, individuals are going to have more money in their pockets which they are likely to dispose of by buying goods and services. This means a greater amount of money is going to be spent on these goods and services. This in turn means that the prices of goods and services are going to increase, all other things being equal.

Given the massive increase in this money creation, the yearly growth rate of our monetary measure for the US jumped to 79% in February 2021 from 6.5% in February 2020 – an average increase of 43%.

How prices are established?

As a rule, a supplier sets the price. After all it is the supplier who offers the goods to the buyers. So it is the supplier who must set the price of a good before he presents the good to the buyers.

In order to secure the price that will improve his lot, the price that the supplier sets must cover his direct and indirect costs and provide a margin for profit. By setting the price, the supplier must make as good an estimate as possible regarding whether he will be able to sell his entire supply at the price set.

The process of making the estimate involves the assessment of the possible responses of the buyers and the possible responses of his competitors — other suppliers. If his estimates are accurate then he makes a profit. By making a profit, the supplier expands his pool of resources, which in turn enables him to attain more ends. His standard of living improves.

Observe that while the cost of production in some cases would appear to be the main factor in price determination, this is not so. Ultimately, it is the evaluation of the buyer that dictates whether the price set by the supplier is going to be realized. Every buyer decides in his own context whether the price paid for a good betters his life and well-being.

If the cost of production were the driving factor behind setting market prices then how would we explain the prices of goods that have no cost because they are not produced — goods that are simply there, like undeveloped land?

Likewise, the cost-of-production theory cannot explain the reason for the high prices of famous paintings.

According to Rothbard,

Similarly, immaterial consumer services such as the prices of entertainment, concerts, physicians, domestic servants, etc., can scarcely be accounted for by costs embodied in a product.(Murray N. Rothbard, "The Celebrated Adam Smith," originally in Economic Thought Before Adam Smith: An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic hought, Vol. I, Edward Elgar Press, 1995; Mises Institute, 2006.)

It follows then that businesses striving to make profits cannot cause increases in the prices of goods and services without the consent of consumers.

Defining what price is

A price of a thing is the amount of money paid for the thing, for example the number of dollars per loaf of bread, or the number of dollars per shirt. The key driving factors here are the amount of dollars and the quantity of goods.

Now, with all other things being equal, an increase in the amount of money paid for goods and services implies that the price of these goods and services is going to be higher. More money is now paid for these goods and services.

In the absence of the increase in the amount of money there cannot be a general increase in prices. If a business raises the price of its goods and consumers have agreed to this increase then consumers are going to have less money to spend on other goods, all other things being equal. Hence, we will have here a specific price increase but not general increase in prices.

Increases in money supply is what inflation is all about

By a popular thinking, it is the role of the central bank to guide the economy onto the path of economic and price stability.

If central bank officials form a view that the economy will fall below the path of economic and price stability, then officials are expected to prevent this decline by monetary pumping. Conversely, if officials are of the view that the economy is likely to overshoot the stable path then they are likely to prevent this by reducing their monetary pumping.

In response to COVID19, and in particular the lockdowns and other restrictions, severe damage to the economy was expected by central bank officials. (The economy was expected to fall strongly below the path of stability). In this case, strong monetary pumping was considered as a welcome move. The strong monetary pumping is believed to have brought the economy onto a stable path.

We suggest that this monetary pumping cannot generate economic stability. The pumping sets in motion an exchange of nothing for something, or the diversion of wealth from wealth generators to the early recipients of the newly pumped money. As a result, this undermines the process of wealth generation and weakens the prospects for economic growth.

As a rule, because of the monetary pumping, individuals are going to have more money in their pockets which they are likely to dispose of by buying goods and services. This means a greater amount of money is going to be spent on these goods and services. This in turn means that the prices of goods and services are going to increase, all other things being equal.

Given the massive increase in this money creation, the yearly growth rate of our monetary measure for the US jumped to 79% in February 2021 from 6.5% in February 2020 – an average increase of 43%.

Allowing for the time lag from changes in money supply to changes in prices it is not surprising that the momentum of the consumer price index displays a massive increase.

Hence, the culprit here is the alleged defender of the economy - the central bank itself. Curiously, very few commentators are mentioning the role of the central bank in fueling general increases in the prices of goods and services. Note that the massive increase in the growth rate of money supply coupled with lockdowns and various other restrictions have intensified the upward pressure on the prices of goods and services. The combination of not enough savings allocated towards the expansion and the enhancement of the production structure coupled with a strong demand for various goods and services due to the massive increase in money supply has resulted in shortages. We suggest that after a time lag prices are likely to increase further to eliminate the emerged shortages.

Could price controls resolve the issue of general price increases?

There is a view that the government should introduce price controls in order to prevent further increase in the prices of some key consumer goods. A policy of restricting price adjustments because of the monetary pumping is going to weaken various marginal producers. Consequently, these producers are likely to move to activities which are not subject to government price controls.

As a result, the supply of some key consumer goods will come under pressure and we may end up seeing a shortage. So rather than benefiting consumers the government policy is going to hurt consumers’ well-beings. Hence, a policy of price controls is likely to increase shortages and the stifling of the production of goods and services. In fact, this could ultimately lead to the imposition of price controls on a large variety of economic activities and even product controls (rationing). This in turn would most likely result in the economic system that resembles the former Soviet Union. (Ludwig von Mises How Price controls lead to Socialism – Mises Wire 14/1 2016.

Conclusion

In response to the recent strong increase in the momentum of prices, some commentators blame businesses’ “price gouging” for this in order to boost their profits. Whilst businesses set prices it is the consumers that determine whether the price set is going to be accepted.

Furthermore, the suggestion by some that there is the need to impose price controls on some essential consumer goods is, if implemented, likely to further stifle the production process. This in turn is likely to produce massive shortages, price rises in other sectors and a severe decline in the living standards of the same individuals whom the government wanted to assist.

Moreover, none of these measures addresses the fact that the major cause behind the recent massive increases in prices is the aggressive pumping of money by the Fed. Hence, what is required to prevent the decline in individuals’ living standards is to close all the loopholes for the generation of money out of “thin air”. Furthermore, to strengthen the buildup of wealth, various controls and regulations imposed on wealth generators should be removed.

Could price controls resolve the issue of general price increases?

There is a view that the government should introduce price controls in order to prevent further increase in the prices of some key consumer goods. A policy of restricting price adjustments because of the monetary pumping is going to weaken various marginal producers. Consequently, these producers are likely to move to activities which are not subject to government price controls.

As a result, the supply of some key consumer goods will come under pressure and we may end up seeing a shortage. So rather than benefiting consumers the government policy is going to hurt consumers’ well-beings. Hence, a policy of price controls is likely to increase shortages and the stifling of the production of goods and services. In fact, this could ultimately lead to the imposition of price controls on a large variety of economic activities and even product controls (rationing). This in turn would most likely result in the economic system that resembles the former Soviet Union. (Ludwig von Mises How Price controls lead to Socialism – Mises Wire 14/1 2016.

Conclusion

In response to the recent strong increase in the momentum of prices, some commentators blame businesses’ “price gouging” for this in order to boost their profits. Whilst businesses set prices it is the consumers that determine whether the price set is going to be accepted.

Furthermore, the suggestion by some that there is the need to impose price controls on some essential consumer goods is, if implemented, likely to further stifle the production process. This in turn is likely to produce massive shortages, price rises in other sectors and a severe decline in the living standards of the same individuals whom the government wanted to assist.

Moreover, none of these measures addresses the fact that the major cause behind the recent massive increases in prices is the aggressive pumping of money by the Fed. Hence, what is required to prevent the decline in individuals’ living standards is to close all the loopholes for the generation of money out of “thin air”. Furthermore, to strengthen the buildup of wealth, various controls and regulations imposed on wealth generators should be removed.

The Fed and low interest rate policy

It is a commonly accepted view these days that the central bank is a key factor in the determination of interest rates. On this way of thinking, the Fed determines the entire interest rate structure by influencing the short-term interest rates.

The central bank influences the short-term interest rates by means of the monetary liquidity. Thus, by buying assets the Fed adds to the monetary liquidity thereby lowering rates. Whilst by selling assets, the exact opposite is taking place.

According to the popular thinking, the Fed also influences the long-term rates, which are seen as an average of current and expected short-term interest rates.

If today’s one year rate is 4% and the next year’s one-year rate is expected to be 5%, then the two-year rate today should be 4.5% ((4+5)/2=4.5%). Conversely, if today’s one year rate is 4% and the next year’s one-year rate expected to be 3%, then the two-year rate today should be 3.5% (4+3)/2=3.5%.

Given the supposedly almost absolute control over interest rates, it is held that the central bank through the manipulations of short-term interest rates can navigate the economy along the growth path of economic prosperity.

For instance, when the economy is thought to have fallen to a path below that of stable economic growth it is held that by means of lowering interest rates the central bank can strengthen the aggregate demand. This in turn it is held is going to be supportive in bringing the economy onto a stable economic growth path.

Conversely, when the economy becomes “overheated” and moves to a growth path above that, which is considered as stable economic growth, then by lifting interest rates the central bank can push the economy back to the path of economic stability.

Again, on this way of thinking, it seems that the central bank is in charge of interest rates and thus the direction of the economy. However, is it the case? Is it valid to hold that the central bank is the key in the determination of interest rates?

Individuals' time preferences and interest rates

According to the founder of the Austrian School of economics, Carl Menger, the phenomenon of the interest is the outcome of the fact that individuals assign a greater importance to goods and services in the present versus identical goods and services in the future.

The higher valuation is not the result of some capricious behaviour, but due to the fact that life in the future is not possible without sustaining it first in the present. According to Carl Menger,

Human life is a process in which the course of future development is always influenced by previous development. It is a process that cannot be continued once it has been interrupted, and that cannot be completely rehabilitated once it has be/come seriously disordered. A necessary prerequisite of our provision for the maintenance of our lives and for our development in future periods is a concern for the preceding periods of our lives. Setting aside the irregularities of economic activity, we can conclude that economizing men generally endeavor to ensure the satisfaction of needs of the immediate future first, and that only after this has been done, do they attempt to ensure the satisfaction of needs of more distant periods, in accordance with their remoteness in time. [Carl Menger, Principles of Economics, New York University Press, 1976 p 154]

Hence, various goods and services that are required to sustain individual’s life at present must be of a greater importance to him than the same goods and services in the future. The individual is likely to assign higher value to the same good in the present versus the same good in the future.

As long as the means at an individual’s disposal are just sufficient to accommodate his immediate needs, he is most likely going to assign less importance to future goals. With the expansion of the pool of means, the individual can now allocate some of those means towards the accomplishments of various ends in the future.

Life sustenance and the zero interest rate

As a rule, with the expansion in the pool of means, individuals are then able to allocate more means towards the accomplishment of remote goals in order to improve their quality of life over time. With paltry means, an individual can only consider very short-term goals, such as making a basic tool. The meager size of his means does not permit him to undertake the making of more advanced tools. With the increase in the means at his disposal, the individual could consider undertaking the making of better tools.

Note that very few individuals are likely to embark on a business venture, which promises a zero rate of return. The maintenance of the process of life over and above hand to mouth existence requires an expansion in wealth. The wealth expansion implies positive returns.

Again, whilst prior to the expansion of wealth the need to sustain life and wellbeing in the present made it impossible to undertake various long-term projects, with more wealth this has become possible.

Does the lowering of the interest rate permit greater capital formation?

Contrary to the popular thinking, a decline in the interest rate is not the driving cause behind the increases in the capital goods investment. What permits the expansion of capital goods is not the lowering of the interest rate but the increase in the pool of savings.

The pool of savings, which comprises of final consumer goods, sustains various individuals that are employed in the enhancement and the expansion of capital goods i.e. tools and machinery. With the increase in capital goods, it will be possible to increase the production of future consumer goods.

Individuals’ decision to allocate a greater amount of means towards the production of capital goods is signaled by the lowering in the individuals’ time preferences i.e. assigning a relatively greater importance to the future goods versus the present goods.

Hence, the interest rate is just an indicator as it were, which reflects individuals’ decisions. (Again, the decline of the interest rate is not the cause of the increase in capital investment. The decline mirrors the individuals’ decision to invest a greater portion of his resources).

In a free unhampered market, a decline in the interest rate informs businesses that individuals have increased their preference towards future consumer goods versus present consumer goods. Businesses that want to be successful in their venture must abide by consumers’ instructions and organize a suitable infrastructure in order to be able to accommodate the demand for consumer goods in the future.

Note that through the lowering of their time preferences individuals have signaled that they have increased savings in order to support the expansion and the enhancement of the production structure.

Central bank easy policies set boom-bust cycles

Observe that in a free unhampered market fluctuations in the interest rate are going to be in line with the changes in consumers’ time preferences. Thus, a decline in the interest rate is going to be in response to the lowering of individuals’ time preferences. Consequently, when businesses observe a decline in the market interest rate they are responding to this by lifting their investment in capital goods in order to be able to accommodate in the future the likely increase in consumer goods demand. (Note again that in a free-market economy a decline in the interest rate indicates that on a relative basis individuals have lifted their preference towards future consumer goods and services versus present consumer goods and services).

As a rule, a major factor for the discrepancy between the market interest rate and the interest rate that reflects individual’s time preferences is the actions of the central bank. For instance, an aggressive loose monetary policy by the central bank leads to the lowering of the observed interest rate. Businesses respond to this lowering by increasing the production of capital goods i.e. tools and machinery in order to be able to accommodate the demand for consumer goods in the future.

Note that the lowering of the interest rate here is not in response to the decline in consumers time preferences. Consequently, businesses by responding to this lowering of the interest rate do not abide any longer by consumers’ instructions. Note that since consumers did not lower their time preferences they did not increase savings to support the increase in the capital goods investment.

Observe; that every economic activity must be funded i.e. individuals engaged in the activity must be allocated the necessary means to support their lives and well-beings. One of the ways to facilitate the necessary funding is for the businesses to utilize borrowings from banks. On account of the easy monetary policy of the Fed and the emerging sense of prosperity banks are finding it attractive to engage in the expansion of lending.

The banks expansion of lending sets in motion an increase in the credit out of “thin air” i.e. unbacked by savings lending. This in turn gives rise to the increase in the growth rate of money supply. Increases in the money supply growth rate make it possible for the businesses to divert to themselves wealth from genuine wealth generators. This in turn undermines the wealth generation process. In this sense, these businesses are setting in motion activities that most likely would not be supported by the free unhampered market economy. These activities, which we label them as bubble activities, are a burden on the wealth generators since they cannot stand on “their own feet”.

As long as wealth generators are producing enough wealth, bubble activities are prospering against the background of increases in the money supply growth rate. Also, note that the expansion in bubble activities weakens the wealth formation. This in turn exerts an upward pressure on the time preference interest rate. (Note that with less wealth at their disposal individuals’ are likely to increase their preference towards present goods versus the future goods).This works towards the widening in the gap between the time preference interest rate and the market interest rate. Once however, the wealth generation process weakens significantly, i.e. when the pool of wealth either stagnates or declines, bubble activities come under pressure.

The demise of these activities as a result of the decline in the pool of wealth sets in motion a severe economic slump. Note again that bubble activities survive on the back of the loose monetary policies of the Fed. (The loose monetary policy diverts to bubble activities wealth from genuine wealth generators. Also, note that bubble activities could come under pressure if the Fed were to tighten its stance).

Because of the widening in the gap between the time preference interest rate and the market interest rate, businesses have overproduced capital goods relatively to the production of present consumer goods. At some stage, by incurring losses, businesses are likely to discover that past decisions with regard to the capital goods expansion were erroneous.

As a result, businesses are likely to attempt to correct the past errors. Observe that whilst an over- production in capital goods results in a boom, the liquidation of the over-production produces a bust. Note that the overproduction is because of the misallocation of resources brought about by businesses not abiding by consumers instructions. The longer the central bank tries to keep the interest rate at very low level the greater the damage it inflicts on the wealth formation process. Consequently, the longer the period of stagnation is going to be.

Conclusions

As long as life sustenance remains the ultimate goal of human beings, they are likely to assign a higher valuation to present goods versus the future goods and no central bank interest rate manipulation is likely to change this. Any attempt by central bank policy makers to overrule this fact is going to undermine the process of wealth formation and lower individual’s living standards. The central bank can manipulate the interest rate to whatever level it desires. However, it cannot exercise a control over the interest rate as dictated by individual’s time preferences. It is not going to help economic growth if the central bank artificially lowers interest rates whilst individuals did not allocate an adequate amount of savings to support the expansion of capital goods investments. It is not possible to replace saved wealth with more money and the artificial lowering of the interest rate. It is not possible to generate something out of nothing as suggested by many commentators.

It is a commonly accepted view these days that the central bank is a key factor in the determination of interest rates. On this way of thinking, the Fed determines the entire interest rate structure by influencing the short-term interest rates.

The central bank influences the short-term interest rates by means of the monetary liquidity. Thus, by buying assets the Fed adds to the monetary liquidity thereby lowering rates. Whilst by selling assets, the exact opposite is taking place.

According to the popular thinking, the Fed also influences the long-term rates, which are seen as an average of current and expected short-term interest rates.

If today’s one year rate is 4% and the next year’s one-year rate is expected to be 5%, then the two-year rate today should be 4.5% ((4+5)/2=4.5%). Conversely, if today’s one year rate is 4% and the next year’s one-year rate expected to be 3%, then the two-year rate today should be 3.5% (4+3)/2=3.5%.

Given the supposedly almost absolute control over interest rates, it is held that the central bank through the manipulations of short-term interest rates can navigate the economy along the growth path of economic prosperity.

For instance, when the economy is thought to have fallen to a path below that of stable economic growth it is held that by means of lowering interest rates the central bank can strengthen the aggregate demand. This in turn it is held is going to be supportive in bringing the economy onto a stable economic growth path.

Conversely, when the economy becomes “overheated” and moves to a growth path above that, which is considered as stable economic growth, then by lifting interest rates the central bank can push the economy back to the path of economic stability.

Again, on this way of thinking, it seems that the central bank is in charge of interest rates and thus the direction of the economy. However, is it the case? Is it valid to hold that the central bank is the key in the determination of interest rates?

Individuals' time preferences and interest rates

According to the founder of the Austrian School of economics, Carl Menger, the phenomenon of the interest is the outcome of the fact that individuals assign a greater importance to goods and services in the present versus identical goods and services in the future.

The higher valuation is not the result of some capricious behaviour, but due to the fact that life in the future is not possible without sustaining it first in the present. According to Carl Menger,

Human life is a process in which the course of future development is always influenced by previous development. It is a process that cannot be continued once it has been interrupted, and that cannot be completely rehabilitated once it has be/come seriously disordered. A necessary prerequisite of our provision for the maintenance of our lives and for our development in future periods is a concern for the preceding periods of our lives. Setting aside the irregularities of economic activity, we can conclude that economizing men generally endeavor to ensure the satisfaction of needs of the immediate future first, and that only after this has been done, do they attempt to ensure the satisfaction of needs of more distant periods, in accordance with their remoteness in time. [Carl Menger, Principles of Economics, New York University Press, 1976 p 154]

Hence, various goods and services that are required to sustain individual’s life at present must be of a greater importance to him than the same goods and services in the future. The individual is likely to assign higher value to the same good in the present versus the same good in the future.

As long as the means at an individual’s disposal are just sufficient to accommodate his immediate needs, he is most likely going to assign less importance to future goals. With the expansion of the pool of means, the individual can now allocate some of those means towards the accomplishments of various ends in the future.

Life sustenance and the zero interest rate

As a rule, with the expansion in the pool of means, individuals are then able to allocate more means towards the accomplishment of remote goals in order to improve their quality of life over time. With paltry means, an individual can only consider very short-term goals, such as making a basic tool. The meager size of his means does not permit him to undertake the making of more advanced tools. With the increase in the means at his disposal, the individual could consider undertaking the making of better tools.

Note that very few individuals are likely to embark on a business venture, which promises a zero rate of return. The maintenance of the process of life over and above hand to mouth existence requires an expansion in wealth. The wealth expansion implies positive returns.

Again, whilst prior to the expansion of wealth the need to sustain life and wellbeing in the present made it impossible to undertake various long-term projects, with more wealth this has become possible.

Does the lowering of the interest rate permit greater capital formation?

Contrary to the popular thinking, a decline in the interest rate is not the driving cause behind the increases in the capital goods investment. What permits the expansion of capital goods is not the lowering of the interest rate but the increase in the pool of savings.

The pool of savings, which comprises of final consumer goods, sustains various individuals that are employed in the enhancement and the expansion of capital goods i.e. tools and machinery. With the increase in capital goods, it will be possible to increase the production of future consumer goods.

Individuals’ decision to allocate a greater amount of means towards the production of capital goods is signaled by the lowering in the individuals’ time preferences i.e. assigning a relatively greater importance to the future goods versus the present goods.

Hence, the interest rate is just an indicator as it were, which reflects individuals’ decisions. (Again, the decline of the interest rate is not the cause of the increase in capital investment. The decline mirrors the individuals’ decision to invest a greater portion of his resources).

In a free unhampered market, a decline in the interest rate informs businesses that individuals have increased their preference towards future consumer goods versus present consumer goods. Businesses that want to be successful in their venture must abide by consumers’ instructions and organize a suitable infrastructure in order to be able to accommodate the demand for consumer goods in the future.

Note that through the lowering of their time preferences individuals have signaled that they have increased savings in order to support the expansion and the enhancement of the production structure.

Central bank easy policies set boom-bust cycles

Observe that in a free unhampered market fluctuations in the interest rate are going to be in line with the changes in consumers’ time preferences. Thus, a decline in the interest rate is going to be in response to the lowering of individuals’ time preferences. Consequently, when businesses observe a decline in the market interest rate they are responding to this by lifting their investment in capital goods in order to be able to accommodate in the future the likely increase in consumer goods demand. (Note again that in a free-market economy a decline in the interest rate indicates that on a relative basis individuals have lifted their preference towards future consumer goods and services versus present consumer goods and services).

As a rule, a major factor for the discrepancy between the market interest rate and the interest rate that reflects individual’s time preferences is the actions of the central bank. For instance, an aggressive loose monetary policy by the central bank leads to the lowering of the observed interest rate. Businesses respond to this lowering by increasing the production of capital goods i.e. tools and machinery in order to be able to accommodate the demand for consumer goods in the future.

Note that the lowering of the interest rate here is not in response to the decline in consumers time preferences. Consequently, businesses by responding to this lowering of the interest rate do not abide any longer by consumers’ instructions. Note that since consumers did not lower their time preferences they did not increase savings to support the increase in the capital goods investment.

Observe; that every economic activity must be funded i.e. individuals engaged in the activity must be allocated the necessary means to support their lives and well-beings. One of the ways to facilitate the necessary funding is for the businesses to utilize borrowings from banks. On account of the easy monetary policy of the Fed and the emerging sense of prosperity banks are finding it attractive to engage in the expansion of lending.

The banks expansion of lending sets in motion an increase in the credit out of “thin air” i.e. unbacked by savings lending. This in turn gives rise to the increase in the growth rate of money supply. Increases in the money supply growth rate make it possible for the businesses to divert to themselves wealth from genuine wealth generators. This in turn undermines the wealth generation process. In this sense, these businesses are setting in motion activities that most likely would not be supported by the free unhampered market economy. These activities, which we label them as bubble activities, are a burden on the wealth generators since they cannot stand on “their own feet”.

As long as wealth generators are producing enough wealth, bubble activities are prospering against the background of increases in the money supply growth rate. Also, note that the expansion in bubble activities weakens the wealth formation. This in turn exerts an upward pressure on the time preference interest rate. (Note that with less wealth at their disposal individuals’ are likely to increase their preference towards present goods versus the future goods).This works towards the widening in the gap between the time preference interest rate and the market interest rate. Once however, the wealth generation process weakens significantly, i.e. when the pool of wealth either stagnates or declines, bubble activities come under pressure.

The demise of these activities as a result of the decline in the pool of wealth sets in motion a severe economic slump. Note again that bubble activities survive on the back of the loose monetary policies of the Fed. (The loose monetary policy diverts to bubble activities wealth from genuine wealth generators. Also, note that bubble activities could come under pressure if the Fed were to tighten its stance).